Perun’s axes

Miniature axes, the so-called Perun’s axes, have been found in Central-Eastern and Northern Europe. But what were these miniature weapons? Were they amulets with magical properties, toys, or perhaps ornaments?

To avoid any misunderstandings—if you expect a clear answer to these questions from this text, you won’t find it here, because no definitive answer exists. Instead, I will attempt to present the available knowledge about them and the hypotheses concerning their function. But first, let us begin with a brief introduction.

Introduction

The concept of miniature weapons was known in various cultures throughout Europe. Miniature weapons are primarily associated with the Germanic peoples of the Roman and Migration Periods. In the area inhabited by the Baltic peoples, there are examples of axes made of amber, and the very idea of miniature axes was known from Ireland to Russia. However, the small hatchets known as “Perun’s axes” are relatively uniform, differing only in minor details.

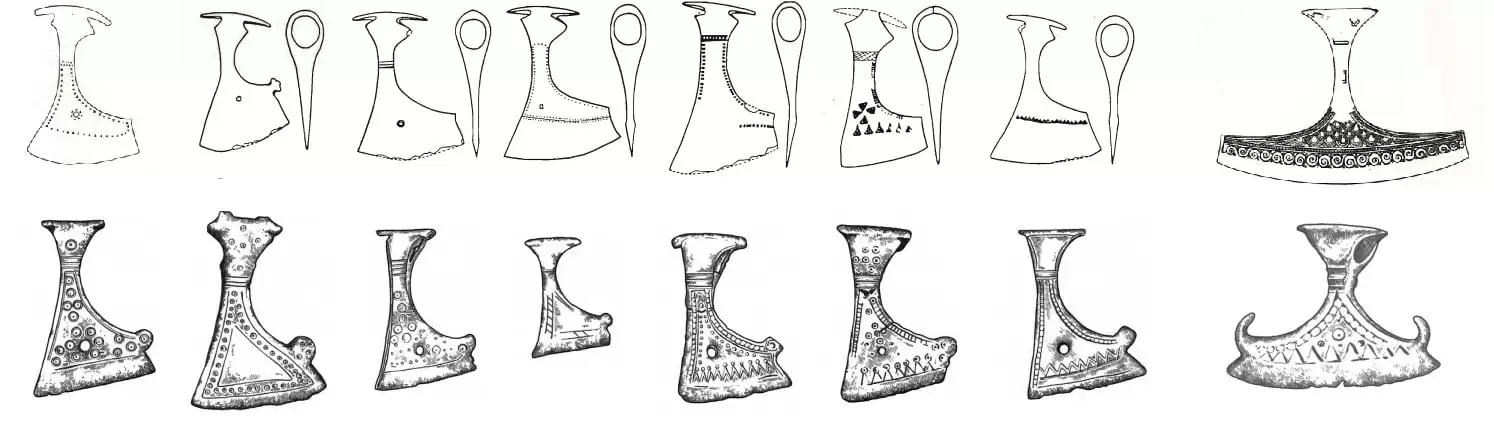

These axes are linked to Slavic culture and were found in Central-Eastern and Northern Europe, dating from the 10th to the 12th century. They were a few centimeters in size and made of metal. Due to the ornaments on them—zigzag lines (possibly representing lightning bolts) and circles (interpreted as solar symbols)—they are associated with the thunderbolt, and thus with Perun.

Among Indo-European peoples, including the Slavs, the axe itself held special significance as a weapon. It often appeared in mythology and rituals and was an attribute of gods, symbolizing power and war. For the Slavs, the axe was linked to a thunder deity, best known by his East Slavic name, Perun, meaning “thunderbolt” or “thunder.” This name derives from the Proto-Indo-European roots per-, perk-, and perg-. Perun was one of the chief Slavic deities, worshipped across Slavonia under different names. His counterparts in other Indo-European religions include the Baltic Perkunas, the Germanic Thor, and the Greek Zeus.

According to Makarov, Perun’s axes can be divided into two types:

:

Type1

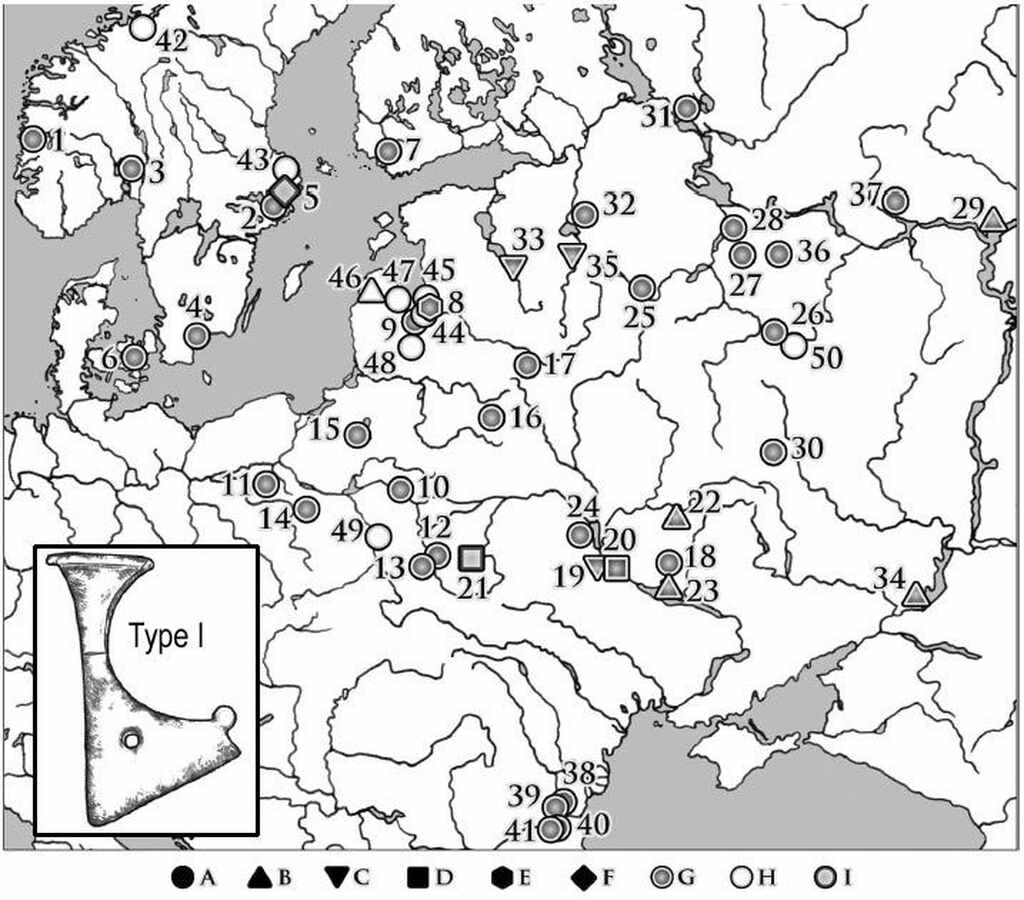

Distribution of Type 1 axe finds (Maps from “The Distribution of Early Medieval Metal Miniature Axes in Central, Eastern, and Northern Europe” by Paweł Kucypera, Piotr Pranke, and Sławomir Wadyl.)

Type 1 is the most numerous group, with 95 axes belonging to this category discovered so far. They were most popular from the 11th century onward. These miniatures replicate real battle axes used in the Slavic region between the 10th and 12th centuries. According to classifications, they are miniature versions of real battle axes: Type 4 according to Kripchimkov or Type 5a according to Nadolsky.

In some specimens, traces of wooden handles—or even remnants of them—have been found. These miniature axes differ from their full-sized combat counterparts in several ways:

- They have schematically outlined whiskers.

- The blade is relatively narrow and almost straight.

- The chin ends in a semi-circular projection, which is uncommon in actual battle axes.

- They feature a hole in the central part of the blade, likely for suspension.

The blades of these axes are often decorated with circular motifs, possibly symbolizing the sun, a biradius with a keel ornament, or engravings. A zigzag line runs along the bottom of the blade, which may symbolize lightning—a reference to the thunder god Perun.

Below are some examples of such axes:

- Examples of miniature axes of Makarov’s type 1 (a–f), similar to type 1 (g–l) and of original forms (m–p). a – Rinkaby, b – Sigtuna, c – Daugmale, d – Sigtuna, e – Hjelmsølille,

- Perun’s axe Type1

- Perun Axe Type 1 with remains of handle

TYPE 2

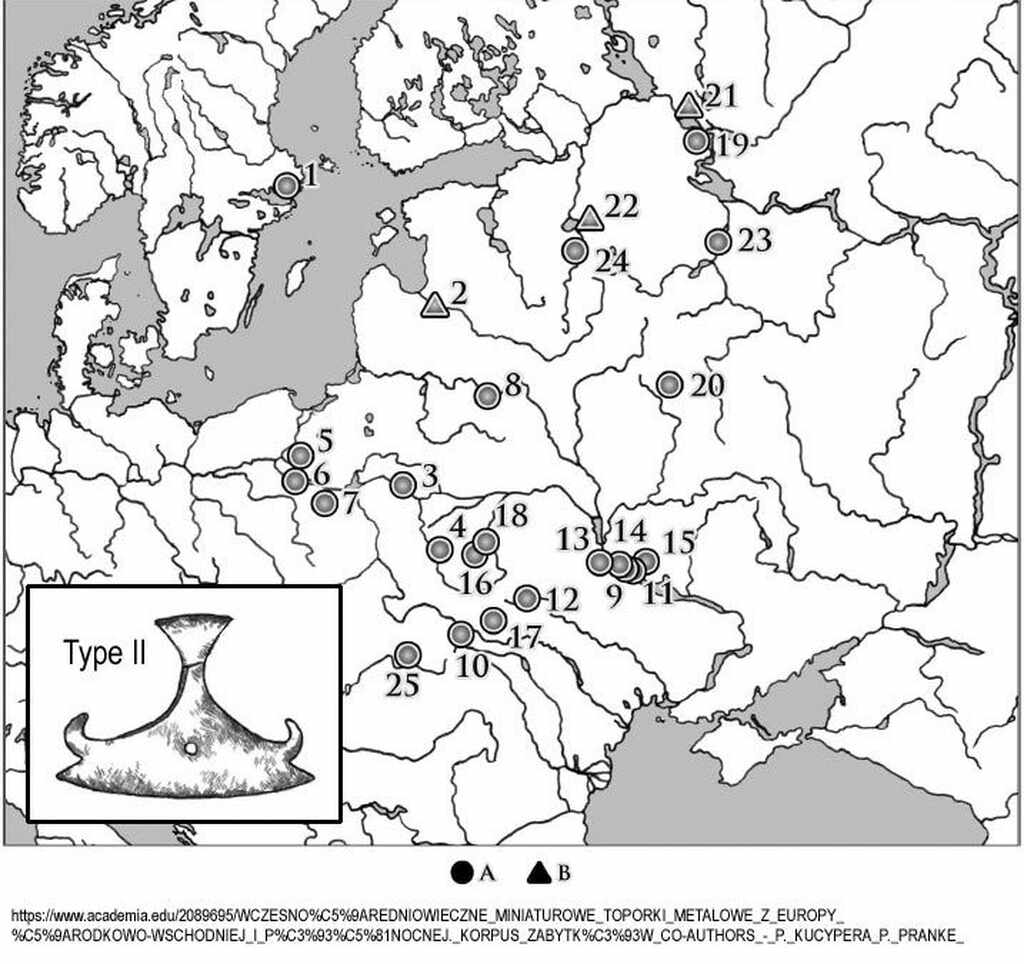

- Distribution of Type 2 axe finds (Maps from “The Distribution of Early Medieval Metal Miniature Axes in Central, Eastern, and Northern Europe” by Paweł Kucypera, Piotr Pranke, and Sławomir Wadyl.)

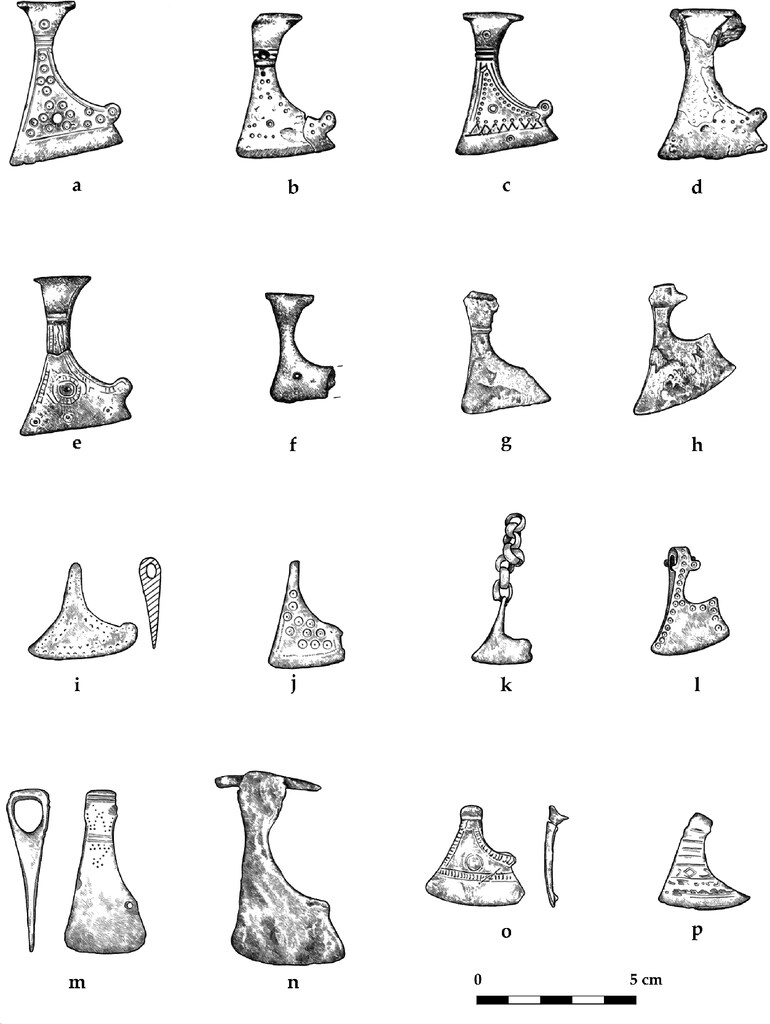

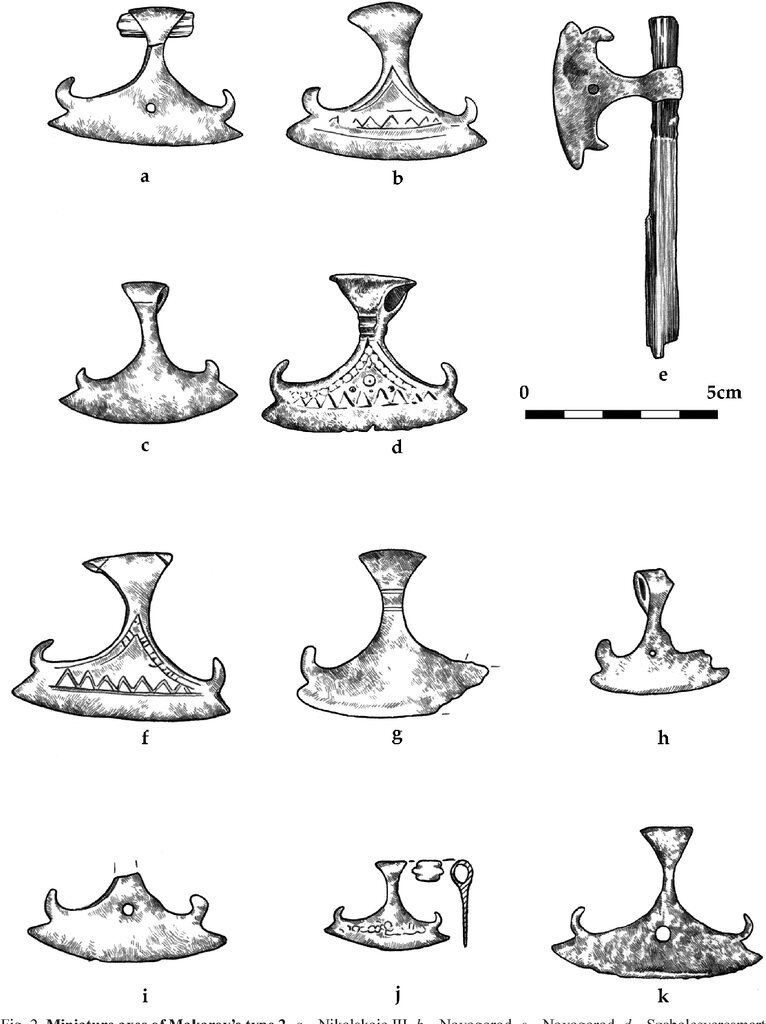

Axes of this type have been found in 30 pieces, of which only five were discovered outside Slavic areas: one in Scandinavia, one in Hungary, and three among Baltic tribes. These axes, made of metal, have blade lengths ranging from 3.5 to 4.3 centimetres and widths from 3.5 to 5.7 centimetres. The blades are symmetrical or nearly symmetrical, with a slight curve along the edge. There are hilt-like protrusions on the inner side, and the neck is narrow, gradually widening at the hilt.

Often, there is a hole in the blade. Fewer than half of the axes feature ornamentation, most commonly in the form of a biordering running along the edge, filled with triangles or transverse/oblique grooves. Several examples feature a zigzag ornament along the blade’s edge, which can be interpreted as a lightning bolt, once again referencing a thunder deity.

Among them, the axe found in Kałdus, Poland, is unique. It is made of bronze, and the blade is inscribed with an image of a boat, featuring prominent rowing figures and shields attached overboard.

There is no consensus among researchers regarding what these axes imitate in form. According to one hypothesis, they reflect an axe with a fan-shaped blade, often found in the southeastern Baltic and Scandinavia in the 10th and 11th centuries. Another hypothesis links them to the shape of a boat, while a third connects them to the form of Thor’s hammer, carried by the Scandinavians. To date, we have no firm evidence to unequivocally confirm or refute either hypothesis.

Some interesting examples of axes include:

- Fig. 2. Miniature axes of Makarov’s type 2. a – Nikolskoje III, b – Novogorod, c – Novogorod, d – Szabolcsveresmart, e – Staraya Russa, f – Kniaża Hora, g – Lipliave, h – Lutsk, i – Tieri

- Perun’s axe Type 2, the second half of the 11th century, Borisoglebsk excavation, Staraya Russa, find of 2000.

- Perun’s axe Type 2 from the Novgorod museum dated to the 11th-12th century, obtained at the Trotsky excavation in Veliky Novgorod

- Miniature axe of 2nd type found in Kałdus, comm. Chełmno, Poland

Non-typical axes

IIn addition to these two types, there are several non-typical hatchets that are difficult to classify into either group. The most interesting of these include the hatchet from Arne, located on the border between Europe and Asia, which resembles a pickaxe rather than an axe; the hatchet from Bilara, with its strongly hooked projection and zoomorphic depictions; and the double-bladed hatchet found in Novgorod. Below are some examples:

- Axe amulet from the Novgorod museum dated to the 11th century, obtained at the Nerivesky site in Novgorod

Function and interpretations

Most of the axes were found in burial grounds, with only a few found in graves. In Poland, of the ten axes discovered in graves, 6 were found in children’s graves, 2 in men’s graves (where they were placed at the hips or thighs), and 2 in women’s graves (where they were found in the chest area, between amulets and beads).

There is no consensus among researchers regarding the function of these hatchets. Some consider them to be jewelry, signifying the social prestige of the wearer, or suggest that they may have served as a cloak fastener or a wedge for securing the hilt of an axe blade, but these theories seem unlikely.

Because these hatchets may be copies of real weapons that were popular in this part of Europe during the 11th century, some scholars associate them with the warrior class. The axes found in children’s graves could indicate that they were given to the sons of warriors during a hair-cutting ceremony at the age of 7, when the boy symbolically passed from his mother’s care to his father’s care. However, this theory is contradicted by the discovery of axes in women’s graves and the lack of axes found in warrior graves, as well as the absence of such finds at Byzantine sites where the Varangians/Russians served in the Byzantine army.

Another hypothesis links the axes to the cult of St. Olaf Haraldson, whose cult was popular throughout much of Europe at the time, from Iceland and Greenland to Byzantium and Novgorod. According to this theory, in the folk tradition, characterized by dualism, St. Olaf took on attributes of both Christ and Thor, and the axe was considered a continuation of Thor’s hammer. In the Slavic area, St. Olaf was naturally identified with Perun.

It is also possible that the axes were worn as amulets and may have had some magical, protective, or curative function, but this remains purely speculative, as there is no concrete evidence to confirm this theory.

The most popular theory links the axes to the cult of Perun, which is supported by the ornamentation found on them: the dotted circle is thought to symbolize the sun, and the zigzags represent lightning. This symbolism aligns with that of Indo-European thunderbolt deities, such as Thor and, more specifically, Perun.

There is no certainty regarding the function of these hatchets. Each theory has supporting arguments, but there are also counterarguments that cannot be easily dismissed. Thank you for reading this article. I hope I have at least provided some insight into this artifact, which was quite popular in this part of Europe during the early Middle Ages.

Bibliography

- Article titled , “Possible function of the ‘Perun Axes’ from https://sagy.vikingove.cz

- ,,Wczesnośredniowieczne miniaturowe toporkimetalowe z Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej i Północnej. Korpus zabytków” by Paweł Kucypera, Piotr Pranke, Sławomir Wadyl from working at ,,Życie codzienne przez pryzmat rzeczy”. University of Mikolaja Kopernika in Torun, 2010.

- ,,Early medieval miniature axes of Makarov’s type 2 in the Baltic Sea Region” by Paweł Kucypera, Sławomir Wadyl

Illustrations

- museum in Greater Novgorod, Russia:

- website arkaim.co:

- maps and drawings from the work ,,Early medieval miniature axes of Makarov’s type 2 in the Baltic Sea Region” by Paweł Kucypera, Sławomir Wadyl

- online store ozdoby-wikingow.pl: